Stahl House, completed in 13 months and costing $37,500, further demonstrated Pierre Koenig’s flair for working with industrial materials, particularly steel, glass and concrete.

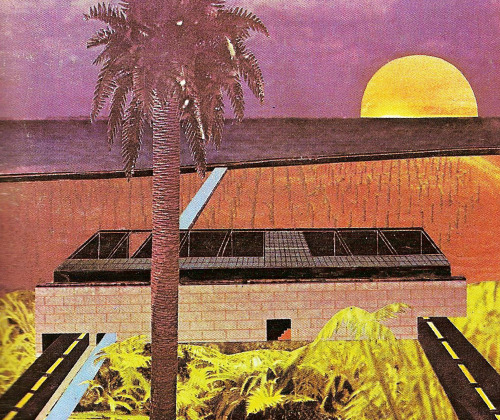

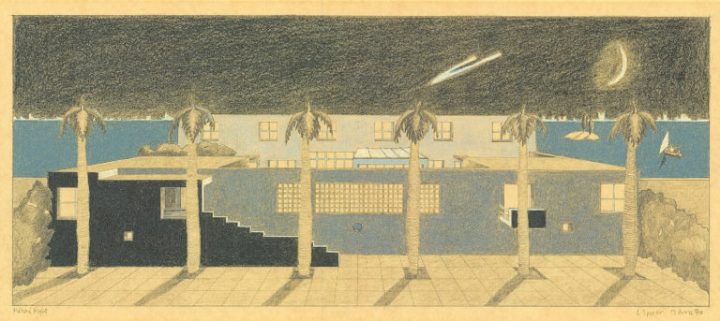

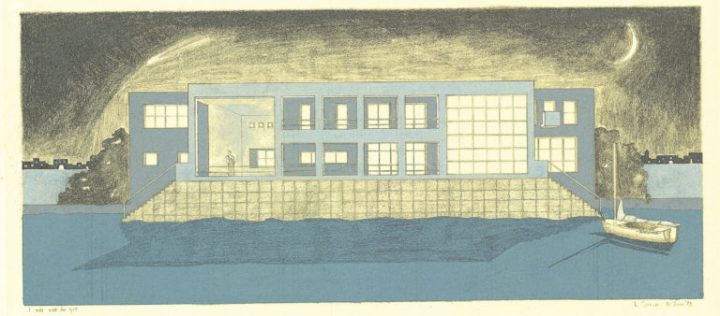

The image is instantly familiar; the house, all dramatic angles, concrete, steel and glass, perched indelibly above Los Angeles, with Hollywood’s lights resembling a circuit board below it. Inside, two women sit, stylish and relaxed, talking casually behind the monumental floor to ceiling glass walls. One of the world’s most iconic photographs, Julius Schulman’s Case Study 22 beautifully captures the optimism of 1950s Los Angeles, and the striking beauty of architect Pierre Koenig’s masterpiece, Stahl House. The classic L shaped pavilion, cantilevered above Hollywood on Woods Drive, was built in 1959 after being adopted into the Case Study Program, an experimental residential design initiative that commissioned architects to create model homes in the wake of the 1950s housing boom. Stahl House, also known as No. 22, was the wild one, conjured up by the man who purchased the plot of land at 1635 Woods Drive in 1954 for $13,500 and sealed the deal with a handshake. C H ‘Buck’ Stahl was a dreamer, who, along with his wife Carlotta, set about finding the right person to bring his vision for an innovative and thoroughly modern home to life.

The image is instantly familiar; the house, all dramatic angles, concrete, steel and glass, perched indelibly above Los Angeles, with Hollywood’s lights resembling a circuit board below it. Inside, two women sit, stylish and relaxed, talking casually behind the monumental floor to ceiling glass walls. One of the world’s most iconic photographs, Julius Schulman’s Case Study 22 beautifully captures the optimism of 1950s Los Angeles, and the striking beauty of architect Pierre Koenig’s masterpiece, Stahl House. The classic L shaped pavilion, cantilevered above Hollywood on Woods Drive, was built in 1959 after being adopted into the Case Study Program, an experimental residential design initiative that commissioned architects to create model homes in the wake of the 1950s housing boom. Stahl House, also known as No. 22, was the wild one, conjured up by the man who purchased the plot of land at 1635 Woods Drive in 1954 for $13,500 and sealed the deal with a handshake. C H ‘Buck’ Stahl was a dreamer, who, along with his wife Carlotta, set about finding the right person to bring his vision for an innovative and thoroughly modern home to life.

Buck was a former professional footballer who worked as a graphic designer and sign painter. He spent his first few years as a landowner hauling broken blocks of concrete to the site in attempt to improve its precarious foundation. He and Carlotta ferried their finds, load by load, back to Woods Drive in the back of Buck’s Cadillac, hopeful the reinforcements would prevent the land from sliding. Buck’s dreams for the house began to take shape over the following two years, and eventually, he made a model of the future Stahl House. His grand designs, however, were promptly rejected by several notable architects.

Buck was a former professional footballer who worked as a graphic designer and sign painter. He spent his first few years as a landowner hauling broken blocks of concrete to the site in attempt to improve its precarious foundation. He and Carlotta ferried their finds, load by load, back to Woods Drive in the back of Buck’s Cadillac, hopeful the reinforcements would prevent the land from sliding. Buck’s dreams for the house began to take shape over the following two years, and eventually, he made a model of the future Stahl House. His grand designs, however, were promptly rejected by several notable architects.

Carlotta recalled Buck continually telling prospective architects “I don’t care how you do it, there’s not going to be any walls in this wing.” Until they hired Pierre Koenig in 1957, an ambitious young architect determined to build on a site nobody would touch, it seemed unlikely the house would ever exist. Pierre described the process of building Stahl House as “trying to solve a problem – the client had champagne tastes and a beer budget.” He was interested in working with steel, and despite being warned away from it by his architecture instructors, possessed great aptitude for it. He’d experimented with a number of exposed glass and steel homes before he created Case Study 21, or The Bailey House in 1958 and 1959, and his skill for designing functional spaces with simplicity of form, abundant natural light, and elegant lines would eventually make him a master of modernism. Stahl House, completed in 13 months and costing 37,500 USD, further demonstrated Pierre’s flair for working with industrial materials, particularly steel, glass, and concrete. The project put him on the map as an architect with an incredible eye for balance, symmetry, and restraint. The 2,040 m² house was, as Buck insisted, built without walls in the main wing to allow for sweeping 270º views. Three sides of the building were made of plate glass, unheard of in the late 1950s, and deemed dangerous by engineers and architects. This design feature required Pierre to source the largest pieces of glass available for residential use at the time. With two bedrooms, two bathrooms, polished concrete floors, and a very famous swimming pool (a fixture in countless films and fashion editorials) Stahl House was an immediate mid century icon.

Carlotta recalled Buck continually telling prospective architects “I don’t care how you do it, there’s not going to be any walls in this wing.” Until they hired Pierre Koenig in 1957, an ambitious young architect determined to build on a site nobody would touch, it seemed unlikely the house would ever exist. Pierre described the process of building Stahl House as “trying to solve a problem – the client had champagne tastes and a beer budget.” He was interested in working with steel, and despite being warned away from it by his architecture instructors, possessed great aptitude for it. He’d experimented with a number of exposed glass and steel homes before he created Case Study 21, or The Bailey House in 1958 and 1959, and his skill for designing functional spaces with simplicity of form, abundant natural light, and elegant lines would eventually make him a master of modernism. Stahl House, completed in 13 months and costing 37,500 USD, further demonstrated Pierre’s flair for working with industrial materials, particularly steel, glass, and concrete. The project put him on the map as an architect with an incredible eye for balance, symmetry, and restraint. The 2,040 m² house was, as Buck insisted, built without walls in the main wing to allow for sweeping 270º views. Three sides of the building were made of plate glass, unheard of in the late 1950s, and deemed dangerous by engineers and architects. This design feature required Pierre to source the largest pieces of glass available for residential use at the time. With two bedrooms, two bathrooms, polished concrete floors, and a very famous swimming pool (a fixture in countless films and fashion editorials) Stahl House was an immediate mid century icon.

Although there has been some dispute over Buck’s influence on the design in the years since he died in 2005 and Pierre Koenig’s death in 2004, some experts who have seen Buck’s original model agree that his concept informed the direction the Stahl House would finally take.

“I dismissed it as typical owner hubris at the time,” architect and writer Joseph Giovannini told the Los Angeles Times in 2009. “The gesture of the house cantilevering over the side of the hill into the distant view is clearly here in this model. But it is Pierre’s skill that elevated the idea into a masterpiece. This is one of the rare cases it seems that there is a shared authorship.”

Today, Stahl House is still owned by the Stahl family. Though it remains a magnet for film crews and photographers the world over, for Bruce Stahl, Buck and Carlotta’s son, who grew up there with his siblings, it was simply part of a typical, happy childhood. “We were a blue collar family living in a white collar house,” he said. “Nobody famous ever lived here.”

Credits: Lucy Brook

Photos: Rick Poon

The

The  This project was the last in a series of private homes known as the ‘white villas’ built by Le Corbusier and his cousin and partner

This project was the last in a series of private homes known as the ‘white villas’ built by Le Corbusier and his cousin and partner  Unfortunately the Villa Savoye presented its residents with its own host of problems, despite its pioneering design. Each autumn, as the windows ushered in a warm vista of seasonal colour, the family would write repeatedly to Le Courbusier, begging him to make ‘habitable,’ what proved to be a damp and chilly building. They complained of ‘raining’ in the hall, on the ramp and in the bathroom. The loud drumming of rain on the bathroom skylight kept them awake at night, heat escaped through the long stretches of glazing and the heating system was both insufficient and a further cause of flooding.

Unfortunately the Villa Savoye presented its residents with its own host of problems, despite its pioneering design. Each autumn, as the windows ushered in a warm vista of seasonal colour, the family would write repeatedly to Le Courbusier, begging him to make ‘habitable,’ what proved to be a damp and chilly building. They complained of ‘raining’ in the hall, on the ramp and in the bathroom. The loud drumming of rain on the bathroom skylight kept them awake at night, heat escaped through the long stretches of glazing and the heating system was both insufficient and a further cause of flooding.

US architecture firm

US architecture firm  The office is located within the upper floor of a 100-year-old building in

The office is located within the upper floor of a 100-year-old building in  The company had occupied a portion of the floor since 2013, and decided to take over the full story when its neighboring tenant moved out. Local firm

The company had occupied a portion of the floor since 2013, and decided to take over the full story when its neighboring tenant moved out. Local firm  The challenge was to create a cohesive open-plan workspace which retained the feel of the original Substantial space and would maximize the existing character of the building – exposed brick walls, old-growth Douglas Fir beams and roof decking, and the beautiful warehouse-style window walls.

The challenge was to create a cohesive open-plan workspace which retained the feel of the original Substantial space and would maximize the existing character of the building – exposed brick walls, old-growth Douglas Fir beams and roof decking, and the beautiful warehouse-style window walls. The architects worked closely with the client to understand day-to-day operations, as well as the company’s love of hosting parties. Their research led to the conception of the office’s signature element: The Forum, an assembly area for social and business activities.

The architects worked closely with the client to understand day-to-day operations, as well as the company’s love of hosting parties. Their research led to the conception of the office’s signature element: The Forum, an assembly area for social and business activities.

The social space was situated near the entry staircase and looks toward a large reception desk faced with a steel door from the old office. The room is illuminated by a large skylight.

The social space was situated near the entry staircase and looks toward a large reception desk faced with a steel door from the old office. The room is illuminated by a large skylight. In the kitchen, the team installed two bars made of cross-laminated timber planks, along with several black dining tables with colorful chairs. Employees can be found working here throughout the day.

In the kitchen, the team installed two bars made of cross-laminated timber planks, along with several black dining tables with colorful chairs. Employees can be found working here throughout the day. Surrounding The Forum are conference rooms, with walls made of black-stained

Surrounding The Forum are conference rooms, with walls made of black-stained