LA OF THOSE SPARKLING BEACHES, EPIC MOUNTAINS, 300 DAYS OF SUNSHINE. LA OF WORK LIFE BALANCE (A REAL THING). LA OF STILL SEMI AFFORDABLE HOUSING. A PHOTOGRAPHER FRIEND AND HIS WIFE WHO WENT LEFT EARLIER THIS YEAR TRADED A DODGY GROUND FLOOR ONE BEDROOM IN BROOKLYN FOR A THREE BEDROOM HOUSE IN HIGHLAND PARK. THEIR RENT? LESS.

“Does it ever stop feeling like a vacation here?” I ask an old friend from New York. He has moved to Los Angeles, and I am visiting. We are sitting in front of the blob of buildings at Sunset Junction in Silverlake. The red paint glows in the sunlight. To our right is coffee temple Intelligentsia, where creative types queue seemingly all day long for a caffeine fix, or set up shop at a grouping of shaded outside tables, laptops clicking. Most people wear sunglasses, most are attractive. To our left, a shop specializes in succulents.

What began with a few souls quietly packing their cars in the night has grown into a full blown westward demonstration. People are leaving New York for LA. And really, why wouldn’t they? LA of those sparkling beaches, epic mountains, 300 days of sunshine. LA of work life balance (a real thing). LA of still semi affordable housing. A photographer friend and his wife who went West earlier this year traded a dodgy ground floor one bedroom in Brooklyn for a three bedroom house in Highland Park. Their rent? Less.

What happened to the strikes that out of towners used to hold against this place? Of plasticity, of vapidity, of a lack of museums, and mediocre at best celebrity chef piloted restaurants. Those have changed, or are in the process of being obliterated altogether. The revitalization of Downtown LA (DTLA if you speak in acronyms) with its booming Grand Central market, scores of hip hotels, eateries, stores, lofts, and apartments has helped shepherd a young creative class to a city sorely lacking one. There are clothing designers cutting denim at Downtown factories, graphic designers tweaking websites in light filled Culver City studios, and the musicians – everyone young and influential in the music industry is camped out here. Artists, too. The average age of guests who line up to get into buzzy, contemporary mecca The Broad? Just 32.

At the opposite end of the LA spectrum, the unflappable and bubbled Hollywood neighborhoods have been altered forever. Beverly Hills, with its Ferrari dealerships and 500 USD dinners, has been left to rot in the hands of the blue hairs. And a recent spin through West Hollywood on a Monday evening found every venue but the venerable Chateau Marmont stone dead. While just around the corner, on West Sunset, the dining room at millennial friendly Thai street food spot Night + Market was packed. (I ate my Pad Thai at the counter.)

“I can’t wrap my head around LA,” my New York fashion friend has said when I’ve brought it up. “Everyone’s eyes are glassed over and they’re telling you: ‘It’s so amazing here!’ Major Kool-Aid vibes.” Admittedly, I’ve loved LA for some time now. In 2009 I visited a friend who had a whitewashed bungalow set back from Abbott Kinney Boulevard in Venice. We sat swapping stories over kale in the backyard of Gjelina, rode our cruiser bikes to the post office to get her mail, and fell asleep in hammocks watching the waves. Everything we did seemed vastly superior to my New York life, which at the time, included twice a day AA meetings and sharing a glorified dormitory on the Upper East Side with not one, but three roommates. “I can’t believe this is your life,” I told her, probably too many times.

It took me seven years, but I finally started sending emails one fall day, harassing the friends who had found their way out to California, asking for a place to crash for the winter months. There was my friend the antique rug dealer over in Eagle Rock, the adventure journalist in Echo Park, the comedian in Santa Monica. The first bite I got back was from the asset manager in Manhattan Beach. “My wife and I have a spare bedroom,” he said on the phone one afternoon. “It’s yours as long as you need it.”

When I pulled into the driveway on a January night, a few days after New Year, I couldn’t believe my luck. Their little house was a block from the crashing water. The spare bedroom was slightly damp in that pleasant way that rooms by the beach are. In the mornings, little slices of sunlight bounced off the stucco ceiling and landed on my face, my forearms. The absence of city noise was alarming at first, but became blissful soon enough. The flinching anxiety took a week or two to melt off. I hiked through the hills. I jogged through town. I wrote. A lot. I lived.

And the asset manager seemed to be living, too. In New York, he’d worn suits, his skin tinted a yellowy grey color. Now he was brown, wore rumpled polo shirts, arrived home by three or four o’clock each afternoon, usually with a heaping bag of fish tacos for dinner. We walked his drooling golden retriever along the beach under the fading orange sun. “We just love it here,” he said, his eyes glowing.

In the LA evenings, I drove and drove. To a house party in Mar Vista. To a bonfire in Glendale. The jaded, that’s too far mentality of any permanent Angelino hadn’t affected me yet, so I drove. During rush hours, and in the middle of the night. To Palm Springs to spend a weekend writing by the pool. To Joshua Tree to watch the sun come up. By the time February rolled around and I was due back in New York, I had a completed manuscript, one I hoped would become a novel. I also had a quandary: Could this place be for me?

Every morning in that guest bedroom, I woke up to three extra hours of emails fired off from the East Coast. Potentially coronary inducing to my New York temperament, right? Not here. No, I’m convinced those several thousand miles did something to shield me from the urgency. Those frantic pleas for revisions and the do or die deadlines seemed like less of a squeeze from out here, like more of a suggestion.

Now, I have no doubt a certain breed of West Coaster would argue, wave their arms in objection. “LA is fast living, man,” they might say. And yeah, relativity is everything – for some, maybe the pace here is less than relaxed. Maybe if you come from Sacramento, or Sausalito. Or maybe the lack of seasons will sterilize you beyond recognition and maybe your eyes will glow, Spicoli-like forever with the vaguely distant tint of a Malibu resident, whose only decision each morning is this: Surf or smoothie? Maybe, just maybe, the 405 will drive you batty.

But I never told you what my old friend said, that morning outside the coffee shop in Silverlake. The friend who had moved to Los Angeles from New York, the friend who said he couldn’t wait to go back East to visit, to flinch, to feel frantic again. He smiled and shook his head when I asked the question: “Does it ever stop feeling like a vacation here?” He said, “No.”

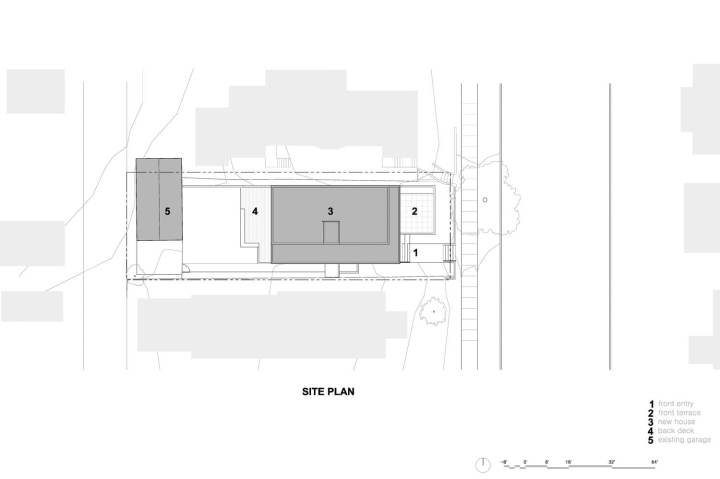

The retreat contains four distinct buildings arranged in two groupings. The first grouping contains the main house, a woodworking shop, and a carport all contained under a single roof in a T-shape. A covered courtyard connects the three spaces in the middle of the “T”. A separate, free-standing artist studio is located just northeast of the main house, with a covered patio that connects to a guest room. Here, the owners work on their own projects, and occasionally host retreats and community-based arts workshops. In all four buildings, large bi-folding doors and sliding barn doors open up the spaces completely to the outdoors, allowing for the movement of large artworks and equipment, as well as an intimate connection with the environment.

The retreat contains four distinct buildings arranged in two groupings. The first grouping contains the main house, a woodworking shop, and a carport all contained under a single roof in a T-shape. A covered courtyard connects the three spaces in the middle of the “T”. A separate, free-standing artist studio is located just northeast of the main house, with a covered patio that connects to a guest room. Here, the owners work on their own projects, and occasionally host retreats and community-based arts workshops. In all four buildings, large bi-folding doors and sliding barn doors open up the spaces completely to the outdoors, allowing for the movement of large artworks and equipment, as well as an intimate connection with the environment.

The main house is minimal in form, consisting of a single double height volume with an open plan living, dining and kitchen area separated from a library by a double-sided fireplace. A set of hidden steel stairs nestled into the concrete fireplace lead to a loft above the library. The home’s single bedroom is located above the bathroom and mudroom and is accessed via a set of open stairs in the entry foyer. Two sets of 30-foot-long bi-fold doors in the main living space allow the home to open completely on both sides, maximizing the home’s sweeping views of the nearby river and Mount Adams.

The main house is minimal in form, consisting of a single double height volume with an open plan living, dining and kitchen area separated from a library by a double-sided fireplace. A set of hidden steel stairs nestled into the concrete fireplace lead to a loft above the library. The home’s single bedroom is located above the bathroom and mudroom and is accessed via a set of open stairs in the entry foyer. Two sets of 30-foot-long bi-fold doors in the main living space allow the home to open completely on both sides, maximizing the home’s sweeping views of the nearby river and Mount Adams.

Main Level

Main Level Second Level

Second Level

Photos by Ryan Siphers

Photos by Ryan Siphers

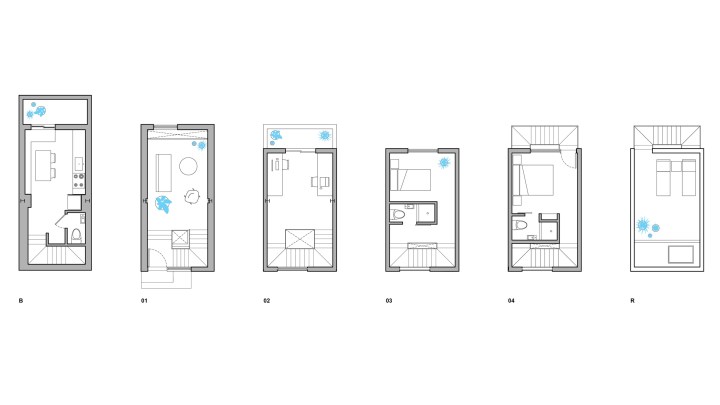

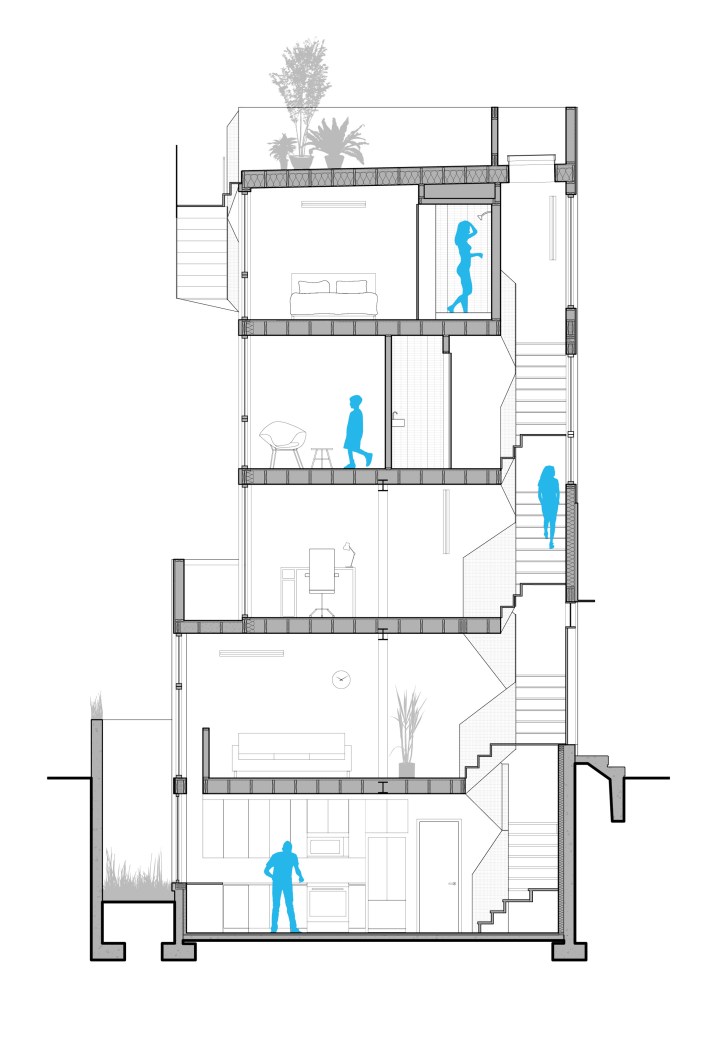

Each of the levels is designed to suit different functions, with the floor space totaling 1,250 square feet (116 sq. meters).

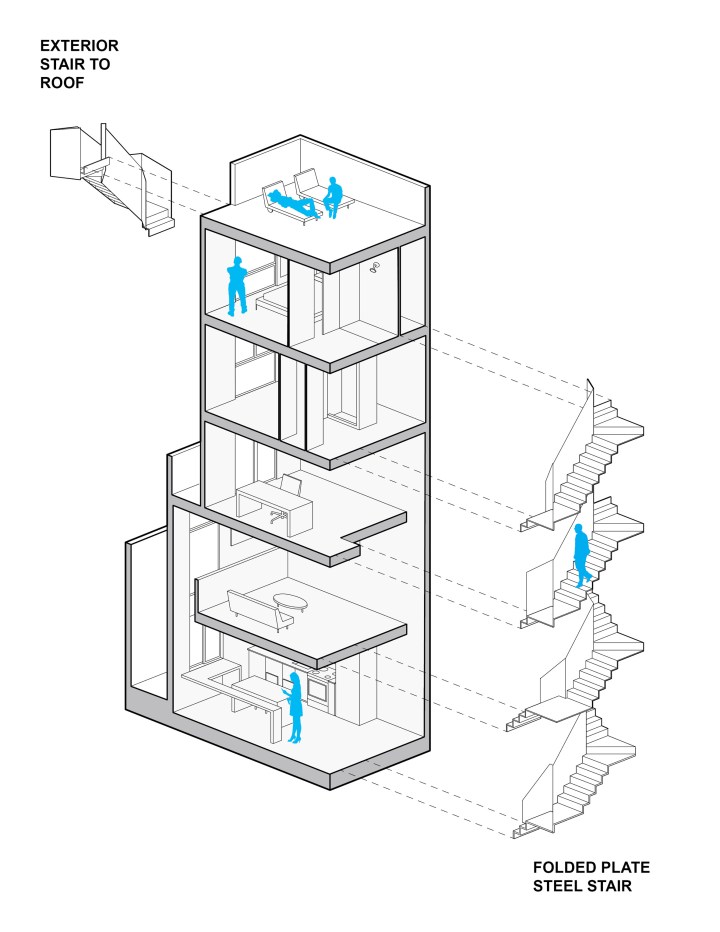

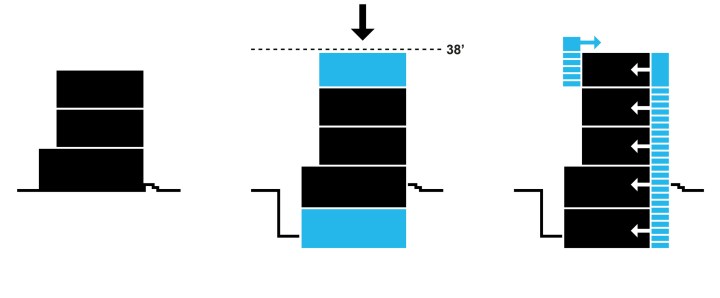

Each of the levels is designed to suit different functions, with the floor space totaling 1,250 square feet (116 sq. meters). Tiny Tower serves as a prototype for flexible-use buildings on small urban plots. Early waves of redevelopment tend to take advantage of sites with standard dimensions, but the area’s urban grid includes many under-utilized extra small parcels facing alley streets.

Tiny Tower serves as a prototype for flexible-use buildings on small urban plots. Early waves of redevelopment tend to take advantage of sites with standard dimensions, but the area’s urban grid includes many under-utilized extra small parcels facing alley streets. The tiered structured stands out from its neighbors, which include parking lots and the gardens of adjacent houses. Rather than a yard, Tiny Tower features a lower level window garden, a second level walk out terrace and a roof deck. The design promotes vertical living for both indoor and outdoor space. The ground floor sits slightly below grade, so the building’s height is not too obtrusive on the surroundings. A further basement level allows for enough living space within the volume squeezed onto the tight plot.

The tiered structured stands out from its neighbors, which include parking lots and the gardens of adjacent houses. Rather than a yard, Tiny Tower features a lower level window garden, a second level walk out terrace and a roof deck. The design promotes vertical living for both indoor and outdoor space. The ground floor sits slightly below grade, so the building’s height is not too obtrusive on the surroundings. A further basement level allows for enough living space within the volume squeezed onto the tight plot.

Unlocking the development potential of these tiny sites is critical as the city looks to increase its supply of low-cost housing for a diverse range of lifestyles. A folded-plate steel staircase at the front of the house connects all five levels, while a separate exterior stair provides access to the roof.

Unlocking the development potential of these tiny sites is critical as the city looks to increase its supply of low-cost housing for a diverse range of lifestyles. A folded-plate steel staircase at the front of the house connects all five levels, while a separate exterior stair provides access to the roof. The lowest level accommodates a kitchen and bathroom. Above, the main entrance opens to the living room a few steps down. The third floor is used as an office, with two desks across from one another and a small balcony.

The lowest level accommodates a kitchen and bathroom. Above, the main entrance opens to the living room a few steps down. The third floor is used as an office, with two desks across from one another and a small balcony.

ISA has also created two other residential projects in Philadelphia: a white townhouse with a plywood core and a housing complex clad in brick, wood and metal.

ISA has also created two other residential projects in Philadelphia: a white townhouse with a plywood core and a housing complex clad in brick, wood and metal.

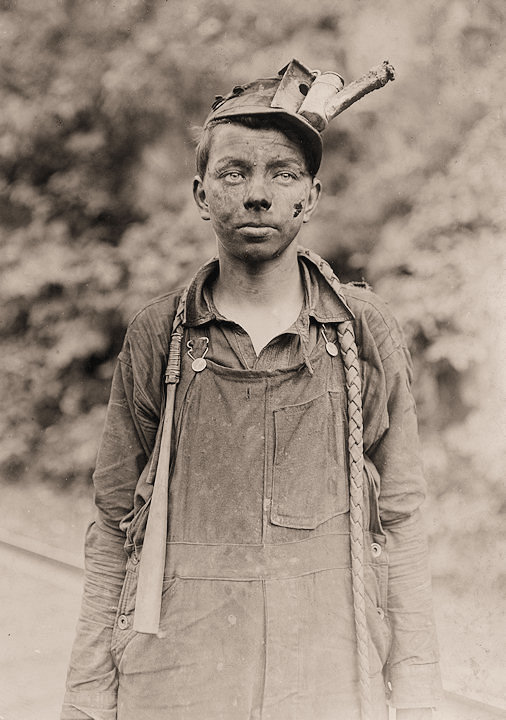

The Factory: Young cigar makers in Engelhardt & Co. Three boys under 14. Labor leaders in busy times employed many small boys and girls. Youngsters all smoke. Tampa, Florida.

The Factory: Young cigar makers in Engelhardt & Co. Three boys under 14. Labor leaders in busy times employed many small boys and girls. Youngsters all smoke. Tampa, Florida.

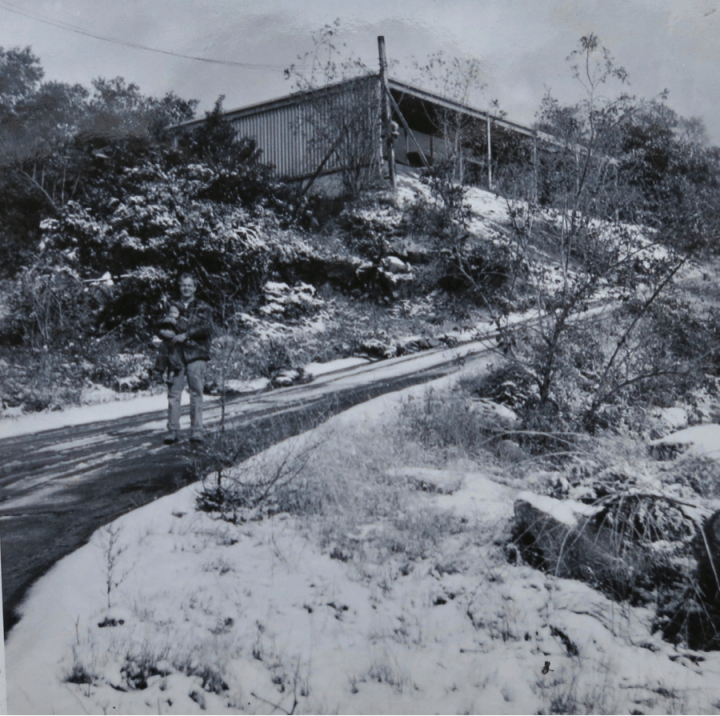

Edwin Scott and his son Mike in front of the Scott House in 1956.

Edwin Scott and his son Mike in front of the Scott House in 1956.

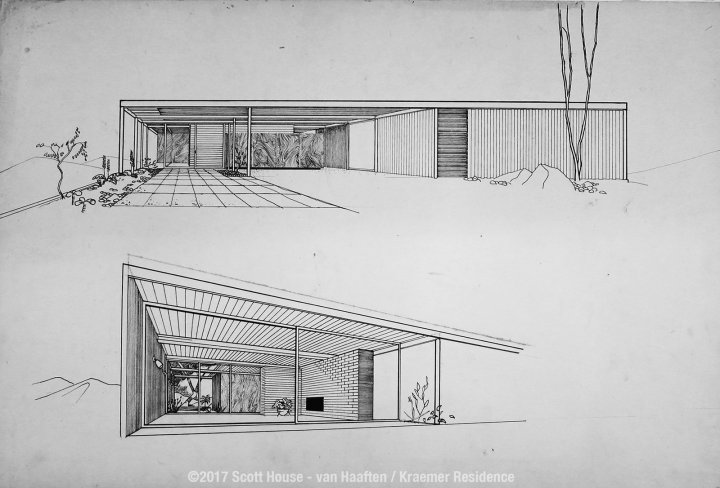

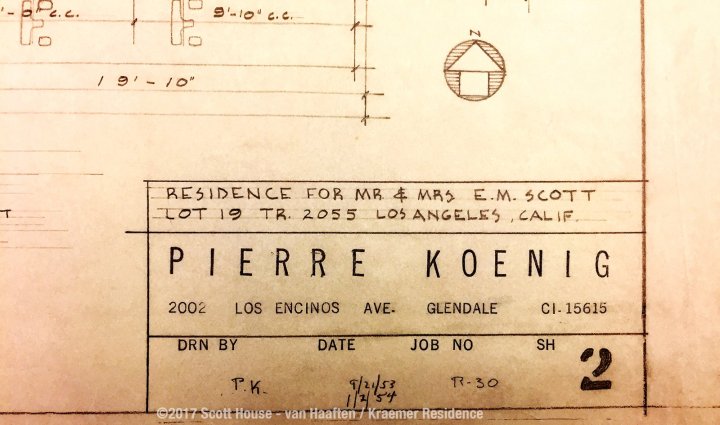

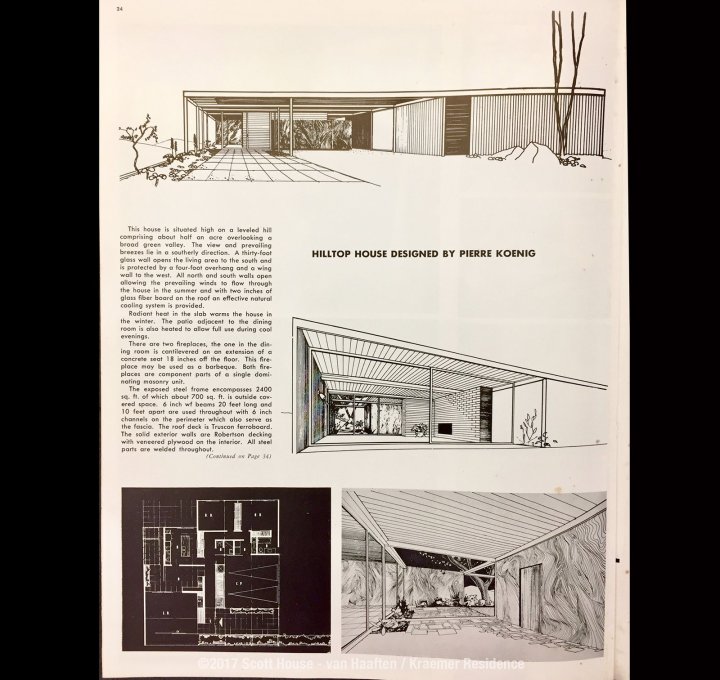

Like many of Koenig’s Case Study Houses, the Scott House is an architecturally simple, L-shaped structure made up of straight, clean lines. Plenty of floor-to-ceiling glass walls link the interior spaces and visually connect the house with its surrounding environment. A bright and expansive central living area is anchored by a dividing wall and a two-sided fireplace. Sliding glass doors connect this central living space to other parts of the house. The kitchen connects to two dining zones: an indoor dining area with a small round table, and a larger “winter garden” dining space with a rectangular table. Full glazing on their exterior walls of the two bedrooms bring in tons of light and allow guests to feel a sense of being immersed in the outdoors.

Like many of Koenig’s Case Study Houses, the Scott House is an architecturally simple, L-shaped structure made up of straight, clean lines. Plenty of floor-to-ceiling glass walls link the interior spaces and visually connect the house with its surrounding environment. A bright and expansive central living area is anchored by a dividing wall and a two-sided fireplace. Sliding glass doors connect this central living space to other parts of the house. The kitchen connects to two dining zones: an indoor dining area with a small round table, and a larger “winter garden” dining space with a rectangular table. Full glazing on their exterior walls of the two bedrooms bring in tons of light and allow guests to feel a sense of being immersed in the outdoors.